Saturday December 22nd… Dear Diary. The main purpose of this ongoing post will be to track United States extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials)😊.

Less Freezing Days, More Rats

It’s no surprise that as winters warm during this century due to climate change we will see some unusual if not detrimental effects. I saw today that yet another outlet, Vox, has implemented a study showing that 67 U.S. cities that traditionally have temperature averages that dip below freezing may not do so soon: https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/12/20/18136006/climate-change-warmer-winters

Quoting Vox:

Crisp white winters are beginning to turn mushy gray across the northern United States. And the longer we wait to get serious about limiting climate change, a White Christmas could become a thing of the past for many cities later this century.

As part of our Weather 2050 project, we examined how average winter low temperatures are projected to shift in the 1,000 largest US cities by 2050 if we do nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In our latest analysis, we found that in 67 cities, the average winter low temperature could cross a critical threshold by 2050: the freezing point of water.

For cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, DC, that have historically snowy winters, this shift in the average winter low means that snow and sleet could become rarer.

Around the country, warmer winters could mean the closure of skating rinks, more pollen, and more ticks carrying Lyme disease, since temperatures won’t be dropping below freezing as often to kill them off. Critical water resources out west that depend on snow will suffer large declines.

“I would argue that our winters are getting sick, and the reason why is global warming,” Amato Evan, an associate professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said at the American Geophysical Union meeting in December.

One way to take winter’s pulse to look at how winter low temperatures are shifting. Here’s a map of the 67 cities we found where the average winter low could shift from below freezing to above freezing by 2050:

(Note that one of the cities is my hometown of Atlanta, which barely has an average minimum of 32 in January as of 2018.)

One way to take winter’s pulse to look at how winter low temperatures are shifting. Here’s a map of the 67 cities we found where the average winter low could shift from below freezing to above freezing by 2050.

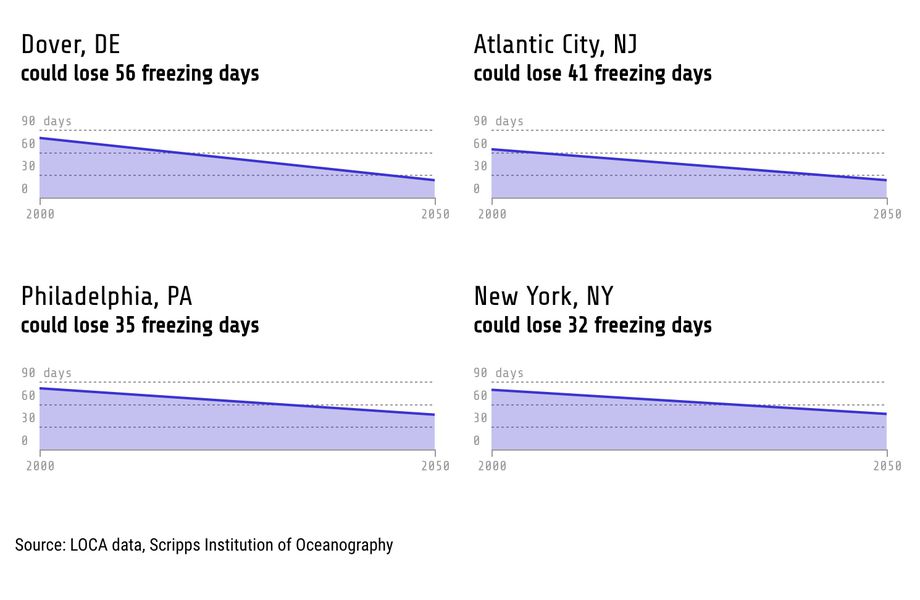

So we also calculated how the number of days with below-freezing temperatures could change by 2050 in the same 67 cities.

Take a look at some cities in the northeastern United States:

Skipping down some of the article, which you might want to read in its entirety:

The loss of freezing days will harm ecosystems, human health, and water resources

In general, scientists expect that winters will warm faster than summers across the US. .

This will have several major consequences that are pretty worrying. For starters, many species are adapted to cold weather and snow, so having fewer or no days below 32°F is sure to impact them. We’re already starting to see those effects.

Animals like the snowshoe hare, found in the boreal forests of Alaska, undergo a seasonal molt from brown in the summer to white in the winter to camouflage with their environment. But less snow in the winter is making them more visible to predators.

Changes in winter temperatures are also starting to affect our health and our water resources.

“Some pests that are [typically] killed off by cold winters are able to thrive and survive,” said Daniel Cayan, a scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

Bark beetles, for example, have devastated forests across the United States as temperatures have risen. In California, bark beetles combined with years of drought have helped kill off 129 million trees across the state. And these dead trees pose a huge wildfire risk: They were one reason the deadly Camp Fire, which torched the town of Paradise, California, in November, got so big so quickly.

Critters that make humans sick are also benefiting from warmer winters. “In regions where Lyme disease already exists, milder winters result in fewer disease-carrying ticks dying during winter,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “This can increase the overall tick population, which increases the risk of contracting Lyme disease in those areas.”

Cold winters have served as a key check on mosquito populations that carry viruses like dengue and Zika. Freezing temperatures can kill off mosquito larvae, reducing their numbers in the spring. But as winters get milder, we’re seeing the range of species like Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus expanding further north and in greater numbers.

Many plants also rely on temperature signals. Seeds detect temperatures to see when it’s appropriate to germinate. Adult plants measure heat and cold to help determine whether to actively grow or go dormant. Some flowering plants are already starting to emerge earlier in the season in part due to warmer winters. This is creating a mismatch between when a plant flowers and when insects like bees are around to pollinate them.

For other plants, like pollen-spewing ragweed, a warmer winter is effectively a shorter winter. That means ragweed and other plants start producing pollen earlier in the season, which will lead to more misery for allergy sufferers.

Another important consequence of winter temperatures rising above freezing is less snowfall. In the western US, the mountain snowpack slowly discharges water as it melts in the spring and summer. The slow release is critical to waterways like the Colorado River to ensure a steady flow.

But the US is now in the midst of a long-term decline in its snowpack, which has already fueled floods in the spring and droughts in the summer. The timing of when the snow melts is also critical. In the Sierra Nevada, earlier snowmelt leads to more wildfires as it leads to a bumper crop of fast-growing vegetation that then dries out in the summer. In some biomes, a dusting of snow can help prevent the ground from freezing, allowing root systems to survive the winter.

The loss of snow and ice is already a major problem for winter recreation. Researchers have found that climate change will shrink the number of days for downhill skiing, cross-country skiing, and snowmobiling across 247 winter recreation areas. For some resorts, the length of skiing season will likely be cut in half by 2050, and across the country, warming winters will cost the industry more than $2 billion.

This all goes to show that we cannot ignore the dramatic changes unmitigated climate change could bring to our winter months.

How we did our analysis

To calculate projections for average winter low temperatures in the 1,000 most-populated cities in the United States, we averaged daily minimum temperatures in winter months for a baseline period over 30 years (1986 to 2015). Then we looked at how these cities would warm by 2050, again averaging over 30 years (2036 to 2065). Since we’re only looking at the continental United States, this analysis does not include Alaska and Hawaii.

These projections are based on a suite of climate models aggregated in the Localized Constructed Analogs data set developed by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

We’re using a standard set of assumptions in climate models known as RCP 8.5. In general, it’s considered a high-end, some would say pessimistic, projection of warming: It assumes that the world will continue on the same course of carbon dioxide emissions with limited improvements in technology or efficiency.

It’s useful because it tracks closely with where we are now and serves as an upper boundary for what we can anticipate. RCP 8.5 also doesn’t result in a vast difference in climate change estimates compared to other scenarios when looking at the middle of the century. The largest variations under RCP 8.5 emerge around 2100.

The biggest unknown is what the world will actually do to address climate change. Nations recently agreed at the latest round of United Nation climate talks in Poland to a set of rules to govern how they implement their pledges to cut emissions under the Paris climate agreement.

But current pledges are not enough to limit warming to 2°Celsius this century above preindustrial levels, the target under the Paris accord. That means countries will still have to do more to fight climate change, drastically slashing fossil fuel use, electrifying their economies, and sucking CO2 out of the air. They’ll also have to adapt to the warming that’s already happening. We can’t escape its effects, even during the coldest times of year.

Special thanks to David Pierce, of the Climate Research Division at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, for guiding the data analysis.

Ah did Vox remember the rats? Evidently not, but here is a second article that did:

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/dec/21/new-york-rat-crisis-climate-change

Quoting The Guardian:

The discarded slices of pizza that litter New York’s streets have long fuelled its sizeable population of rats, but now the city’s growing swarm has a new reason to enjoy their home – warming temperatures.

City officials have reported an increasing number of calls from residents complaining about rats, and have warned that milder winters are helping them feed and mate longer into the year. And as winters warm up, more frequent outdoor activity by humans is adding to the litter rats thrive upon.

Rat-related complaints have been on the rise over the past four years, with 19,152 calls made to the city last year, an increase of about 10% on 2016. There are no reliable figures on the number of rats in New York – estimates range from 250,000 to tens of millions – but the surge in rat activity has been replicated in other cities. Houston, Washington, Boston and Philadelphia have experienced large increases in calls to pest control.

Veteran anti-rat strategists have, in part, blamed climate change. “It’s a complex issue but we are seeing rat population increases around the world now,” said Bobby Corrigan, a sought-after rat-catching consultant who once spent a week living in a rat-infested barn in Indiana as part of his PhD research.

“Requests for my services are through the roof, I can’t keep up with them,” he said. “You speak to any health commissioner from Boston to DC and the trend is upwards.

“In winter rats slow down their reproduction because it’s so cold, but they are probably having one more litter a year now because it’s getting warmer. A litter is around 10 babies and that’s making a difference.”

Mike Deutsch, a veteran rat-catcher at the New York-based Arrow Exterminating Company, said warming temperatures are having a “natural consequence. As the earth warms you’ll have more activity, more rats about. They won’t be able to keep growing if there’s not enough food or shelter for them but you’ll see populations rise.”

Deutsch – whose recent research found that, contrary to popular belief, cats aren’t very good at catching rats – also pointed to other factors such as urban construction that has disturbed rat families, making them more visible.

The increase in rat sightings has spawned viral videos of rats eating pizza and navigating escalators – but has also raised health concerns.

A death was recorded in the Bronx last year due to leptospirosis, a rare disease transmitted via rat urine. New York rats trapped and tested by Columbia University researchers were found to be reservoirs of E coli and salmonella, with some even carrying Seoul hantavirus, which can cause kidney failure.

The city’s response has been muscular. Mayor Bill de Blasio unveiled a $32m plan last year to launch a mass slaughter of rats in infested areas such as Chinatown and the East Village. New York City makes about 100,000 inspections for rat activity each year, and exterminators gas rats to death in their burrows rather than poison them, because of fears over the impact on other wildlife.

De Blasio noted darkly that he’s seen “many a rat” in the city. “I see them in the parks, and in the subway. We’re kind to rats. We just want them to go away.”

However, New York is likely to remain a haven for rats because of its large human population, sprawl of hole-ridden buildings and its copious waste. A warming climate will only exacerbate these rat-friendly conditions.

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity.)

What If The National Weather Service Really Shut Down? via @forbes https://t.co/50lvdKNjvC

— Marshall Shepherd (@DrShepherd2013) December 22, 2018

#CLIMATECHANGE China and Russia testing technology that could modify the atmosphere – concerns that such facilities could be used to modify weather create natural disasters, hurricanes, cyclones and earthquakes. , reports suggest https://t.co/gHOtaLEOnm via @businessinsider

— GO GREEN (@ECOWARRIORSS) December 22, 2018

Fast-intensifying Tropical Cyclone Cilda made a run at Category 5 strength on Friday in the SW Indian Ocean https://t.co/jirnBNEyiS pic.twitter.com/r631kGl3Ax

— Weather Underground (@wunderground) December 22, 2018

(If you like these posts and my work please contribute via the PayPal widget, which has recently been added to this site. Thanks in advance for any support.)

The Climate Guy